Seeking United Latin America, Venezuela's Chávez Is a Divider

By JUAN FORERO

Published: May 20, 2006

BOGOTÁ, Colombia, May 19 — As Venezuela's president, Hugo Chávez, insinuates himself deeper in the politics of his region, something of a backlash is building among his neighbors.

Mr. Chávez — stridently anti-American, leftist and never short on words — has cast himself as spokesman for a united Latin America free of Washington's influence. He has backed Bolivia's recent gas nationalization, set up his own Socialist trade bloc and jumped into the middle of disputes between his neighbors, even when no one has asked.

Some nations are beginning to take umbrage. The mere association with Mr. Chávez has helped reverse the leads of presidential candidates in Mexico and Peru. Officials from Mexico to Nicaragua, Peru and Brazil have expressed rising impatience at what they see as Mr. Chávez's meddling and grandstanding, often at their expense.

Diplomatic sparring has broken into the open. Last month, after very public sniping between Mr. Chávez and Peru's president, Alejandro Toledo, the country withdrew its ambassador from Caracas, citing "flagrant interference" in its affairs.

"He goes around shooting from the hip and shooting his mouth off, and that has caused tensions," Jorge G. Castañeda, a former Mexican foreign minister, said by phone from New York, where he is teaching at New York University. "The difference now is that he's picking fights with his friends, not just his adversaries."

Some of Mr. Chávez's gestures, like his tendency to tweak the Bush administration, or the aid projects he has bankrolled with Venezuela's oil money, still leave him popular, particularly among the poor.

But increasingly, the very image of the Venezuelan leader has come to stand for a style of caustic nationalism that many in the region fear, as the divisions provoked by the man who professes to want to unify his region have widened.

"He is beginning to overreach, wanting to be involved in everything," said Riordan Roett, director of Latin American studies at Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies. "It's a matter of egomania at work here."

Mr. Chávez, for instance, has taken the uncompromising stand that governments must choose either his vision of continental unity or free trade with Washington, which Mr. Chávez blames for impoverishing the region. "You either have one or the other," he said. "Either we're a united community or we're not."

In late April, he exasperated Colombia, Ecuador and Peru by declaring that Venezuela would drop out of their trade group, the Andean Community of Nations, because the other three members were seeking free trade agreements with the United States. He has instead formed a trade bloc with Cuba and Bolivia's new Socialist government.

While the move was filled with political symbolism, analysts say it offers few real prospects for trade and threatens badly needed integration among Andean countries, which still depend on United States markets.

"Chávez's idea of sovereignty seems pretty selective," said Michael Shifter, a senior policy analyst at the Inter-American Dialogue policy group in Washington. "Chávez has been saying, in effect, 'You're either with us or against us.' For most Latin Americans that hubristic message doesn't go over very well, whether it comes from Washington or Caracas."

The sparring with Peru's government erupted last month after President Toledo said it made no sense for Mr. Chávez to criticize his Andean partners for dealing with Washington when Venezuela sells most of its oil to the United States.

But he saved his strongest words for Mr. Chávez's general involvement in Peruvian affairs.

"Mr. Chávez, learn to govern democratically," Mr. Toledo said. "Learn to work with us. Our arms are open to integrate Latin America, but not for you to destabilize us with your checkbook."

When Alan García, a candidate in Peru's June 4 presidential election, also took Mr. Chávez to task, the Venezuelan president responded with, among other things, an endorsement of his opponent.

"I hope that Ollanta Humala becomes president of Peru," Mr. Chávez declared, backing Mr. García's nationalist opponent, who has modeled himself on the Venezuelan leader. "Go, comrade! Long live Ollanta Humala! Long live Peru!"

Mr. Chávez called Mr. García, a former president whose tenure was marred by corruption scandals, "shameless, a thief," and warned that if he were elected "by some work of the devil," Venezuela would withdraw its ambassador.

But it was Peru that made the move first. Venezuela soon followed, and the Chávez government responded by calling Mr. Toledo an "office boy" for President Bush. Mr. García benefited handsomely, taking a long lead in the polls.

Surveys showed Peruvians had little patience for Mr. Chávez's interference. Only 17 percent of Peruvians said they had a positive view of the Venezuelan leader, the Lima-based Apoyo polling firm found.

In Nicaragua, Mr. Chávez has thrown his support behind Daniel Ortega, the former leader of the communist Sandinista revolution, who is running for president in November elections.

"I shouldn't say I hope you win because they will accuse me of sticking my nose into Nicaraguan internal affairs," Mr. Chávez told Mr. Ortega, who was invited on his radio show in late April. "But I hope you win."

Mr. Chávez pledged to supply cheap fuel to a group of Sandinista-run towns. The gesture was interpreted by opponents as a naked ploy to influence the vote and criticized as a backhanded way to funnel money to the Ortega campaign.

Nicaragua's government called on Mr. Chávez to stay out. "We hope this partisan support comes to an end so that Nicaraguans can freely choose who we want to be the next leader of Nicaragua," Foreign Minister Norman Caldera told Nicaraguan television this month.

The American ambassador to Nicaragua, Paul A. Trivelli, speaking to Nicaraguan media, accused Mr. Chávez of "direct intervention," but analysts said it was too soon to say what effect Mr. Chávez would have on the vote.

In Mexico, the leftist candidate in the July presidential election, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has labored to distance himself from Mr. Chávez, to no avail.

When he made a slip of manners recently, calling President Vicente Fox a chattering bird and telling him to shut up, his conservative opponent, Felipe Calderón, ran a series of attack advertisements intercutting the gaffe with images of Mr. Chávez, whose tendency to hurl insults is a trademark. (He has called Mr. Bush a drunkard and Mr. Fox a "puppy dog of the empire.")

In recent weeks, Mr. López Obrador's lead in the polls has evaporated, and he now trails his opponent.

The disputes are not limited to politics, however, but also touch important national interests.

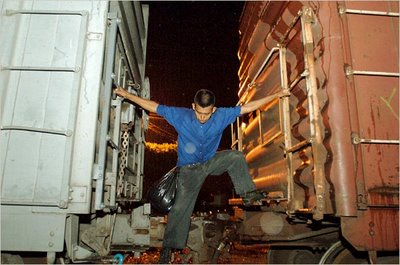

Mr. Chávez, for instance, encouraged and quickly supported Bolivia's nationalization of its energy sector this month, a move that infuriated Argentina and Brazil, which depend on Bolivian natural gas.

Though Venezuela was not a party to the dispute, Mr. Chávez joined a meeting of leaders from Brazil, Argentina and Bolivia aimed at calming the crisis, and dominated a news conference afterward, upstaging even his Bolivian protégé, President Evo Morales.

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil, steward of South America's largest economy and nominally a left-wing ally of Mr. Chávez, was particularly humiliated. Celso Amorim, the foreign minister, was called before senators and quizzed about Brazil's weak response. He said Mr. da Silva had admonished the Venezuelan leader in a private phone call, telling him that the Bolivian move could jeopardize Mr. Chávez's dream of a 5,000-mile pipeline to carry Venezuela's gas to Argentina.

Mr. da Silva also rebuked Mr. Chávez, he said, for involving himself in a dispute that Brazil is having with Uruguay and Paraguay over their trade bloc, Mercosur, saying Mr. Chávez's role was "a stimulant to activities incompatible with the spirit of integration."

The wounds have yet to heal. Jorge Viana, the governor of Acre state in Brazil, and a crucial ally of Mr. da Silva, told Brazilian radio last week that Mr. Chávez's meddling was "lamentable." He criticized Mr. Chávez's "precipitated decisions to interfere in the internal affairs of Bolivia, Peru and, by extension, those of Brazil." Mr. Chávez, he said, "needs to calm down."

James C. McKinley contributed reporting from Mexico City for this article, and Paulo Prada from Rio de Janeiro.

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/20/world/americas/20chavez.html?pagewanted=1&_r=1&th&emc=th