Mexico Worries About Its Own Southern Border

By GINGER THOMPSON

Published: June 18, 2006

TAPACHULA, Mexico, June 11 — Quiet as it is kept in political circles, Mexico, so much the focus of the United States' immigration debate, has its own set of immigration problems. And as elected officials from President Vicente Fox on down denounce Washington's plans to deploy troops and build more walls along the United States border, Mexico has begun a re-examination of its own policies and prejudices.

Here at Mexico's own southern edge, Guatemalans cross legally and illegally to do jobs that Mexicans departing for the north no longer want. And hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants from nearly two dozen other countries, including China, Ecuador, Cuba and Somalia, pass through on their way to the United States.

Dense jungle makes establishing an effective law enforcement presence along the line impossible. Crossing the border is often as easy as hopping a fence or rafting for 10 minutes. But, under pressure from the United States, Mexico has steadily increased checkpoints along highways at the border including several posts with military forces.

The Mexican authorities report that detentions and deportations have risen in the past four years by an estimated 74 percent, to 240,000, nearly half along the southern border. But they acknowledged there had also been a boom in immigrant smuggling and increased incidents of abuses and attacks by corrupt law enforcement officials, vigilantes and bandits. Meanwhile, the waves of migrants continue to grow.

Few politicians have made public speeches about such matters. But Deputy Foreign Minister Gerónimo Gutiérrez recently acknowledged that Mexico's immigration laws were "tougher than those being contemplated by the United States," where the authorities caught 1.5 million people illegally crossing the Mexican border last year. He spoke before a congressional panel to discuss "Mexico in the Face of the Migratory Phenomenon."

In an interview, Mr. Gutiérrez said Mexico needed to "review its laws in order to have more legitimacy when we present our points of view to the United States."

Another high-level official in the Foreign Ministry was more blunt, but spoke only on condition of anonymity because he did not want to be seen as undermining Mexico in its dealings with the United States.

"Are we where we should be in the treatment of migrants?" the official said. "No we are not. But is the Mexican government aware of that? Yes, and it is something we are trying to correct."

Unlike the immigration debate in the United States, where immigration opponents and proponents bandy about estimated costs and benefits for everything from the agriculture industry to suburban horticulture, hard numbers on the effects of illegal migration on Mexico are rare. A trip to Chiapas raises questions about whether Mexico practices at home what it preaches abroad.

If the major characters in the migration drama unfolding in Chiapas could be captured in a collage, it would include a burly, white-haired farmer named Eusebio Ortega Contreras, who did not hide that most of the workers who picked mangos in his fields for $6 a day were underage, undocumented Guatemalans. Indians from Chiapas used to do these jobs, Mr. Ortega said. But in the past five years, they have been migrating to the United States. And lately, he said, he has begun to worry that he is going to lose the Guatemalans, too.

"We know that the conditions we provide our workers are not adequate," said Mr. Ortega, president of the local fruit growers' association, who showed a reporter the meager shelter he can offer: an awning off a hay shed for a roof and lined-up milk crates for beds. "But costs are going up. Production is going down. We barely earn enough money to maintain our orchards, much less improve conditions for the workers."

Joaquín Aguilar Vásquez, a 22-year-old father of two, would be standing with his knapsack in front of a passenger bus for the northern border, because jobs here at home barely kept his family fed. He said he started migrating two years ago to work in an electronics factory in Tijuana, where he earned $12 a day and saved enough to build a house. When he reaches Tijuana this time, he said, he will hire a smuggler to sneak him to a construction job in New Orleans.

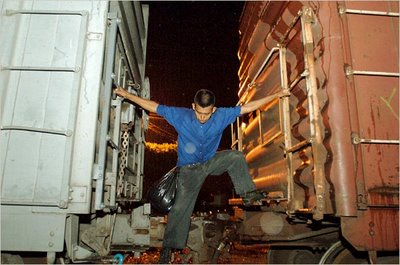

There would be a skinny unidentified Chinese citizen, chain-smoking in the new migration detention center after being caught with more than 50 of his countrymen stowed away among banana crates in the back of a tractor-trailer. Next to him would be a group of Cuban rafters who floated to Mexico because of the increased United States Coast Guard presence around Florida. And there would be a flock of Central Americans, so scruffy and tough they seemed right out of "Oliver Twist," hopping a freight train north.

In the collage, Edwin Godoy, a 21-year-old Honduran who said he was deported last year from Miami and separated from his wife and two children, would be posing in front.

"They call this train the beast," Mr. Godoy shouted in English to get attention. "Do you want to know why? Because it can either take you where you want to go, or it can kill you. Some of us won't make it out of here alive."

At the start of his presidency nearly six years ago, Mr. Fox pledged that, as part of negotiations with the United States for legal status for illegal Mexican immigrants, this country would crack down on the flow of illegal immigrants crossing from Guatemala. He talked of a so-called Southern Plan that was to be an "unprecedented effort," and the United States offered an estimated $2 million a year to help Mexico deport illegal Central American immigrants.

George Grayson, an expert on Mexico at the College of William and Mary who has made several research trips to Mexico's southern border, said little had come of those efforts. He described this border as an "open sesame for illegal migrants, drug traffickers, exotic animals and Mayan artifacts."

And Mr. Grayson said the United States ended its support for deportation after the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security, which instead provides some technical aid and training to increase security at Mexico's southern border checkpoints.

Mexican migration officials acknowledged that they had fewer than 450 agents patrolling the five states along this frontier, which has some 200 official and unofficial crossing points.

The rains came recently and flooded most rivers, making parts of this border as treacherous as the Sonora Desert, the deadly Arizona gateway where more than 460 migrants died of exposure and dehydration last year. But human rights advocates and government migration officials say nature does not do as much harm here as crime and corruption.

The Rev. Ademar Barilli, a human rights advocate who, with the support of the Roman Catholic Church, runs a shelter for migrants in Tecún Umán, a Guatemalan border city, said that unlike crossing patterns at the northern border, migrants here did not typically go far into remote areas, hoping to avoid the authorities. Instead, he said, the migrants try to bribe their way through.

"A migrant with money can make it across Mexico with no problems," Father Barilli said. "A migrant with no money gets nowhere."

Mexican law authorizes only federal migration agents and federal preventive police officers to inspect cars for illegal migrants and to demand proof of legal status. But Mexican authorities acknowledge that migrants face run-ins with every level of law enforcement.

Migrants are also routinely detained by machete-wielding farmers, who extort their money by threatening to turn them over to the police. So many female migrants have been raped or coerced into sex, the authorities said, that some begin taking birth control pills a few months before embarking on the journey north.

Few are punished for such crimes, the authorities added, because the migrants rarely report them.

"This society does not see migrants as human beings, it sees them as criminals," said Lucía del Carmen Bermúdez, coordinator for a government migration agency called Grupo Beta. "The majority of the attacks against migrants are not committed by authorities, although there is still a big problem with corruption in Mexico. Most violence against migrants comes from civilians."

Grupo Beta is a uniquely Mexican creation; established 16 years ago in Tijuana to protect migrants. It was a time, said Pedro Espíndola, the director of Grupo Beta, when Mexican migration to the United States began to soar, and smuggling groups evolved from small-time, community-based operations into transnational criminal cartels.

Grupo Beta was expanded to the southern border in 1996, Mr. Espíndola said, when throngs of Central American migrants, aiming for the United States, began hopping freight trains in Tapachula. Train stations became easy staging areas for gangs to ambush migrants. Hospitals became overwhelmed with men and women who had fallen beneath moving locomotives, often losing limbs to their wheels.

Last year, Grupo Beta reported, 72 migrants died crossing the southern border, mostly in accidents on trains or highways. Human rights groups say the real figure is more than twice as high. And in the 16 years since one woman, Olga Sánchez Martínez, began selling bread and embroidery to operate a shelter and then a clinic for migrants, she said, she has treated more than 2,500 migrants with machete and gunshot wounds or severed limbs.

Last year's rains did so much damage to the bridges and roads around Tapachula that the train does not stop here anymore. But that has not stopped the migrants.

Some detour north of here, the authorities said, to train stations that run through the state of Tabasco. But migrants like Mr. Godoy, the Honduran, have so far refused to abandon this route. He walked eight days along the tracks that run from here to the station in Arriaga, about 120 miles away. Then he, along with at least 300 others, hopped a freight train that leaves there almost nightly, in plain view of evening traffic, the local police and the train's engineer.

It was Mr. Godoy's third attempt in three months. He said he had been caught by United States Border Patrol officers in Laredo, Tex., on each of his previous trips.

"I am not going to give up," he said. "I had a good life in Miami. I got no criminal record. I never hurt nobody. I'm just trying to be with my kids, you know? That's all I need."

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home